Lighting design has been around for a time, and a lighting designer takes home a Tony each year—presented off-camera, before the big event. Critics mention it only occasionally, and rarely with understanding. Maybe that’s because audiences, critics, and award voters don’t fully understand lighting. So we thought we’d try to illuminate it.

Read Part One and Part Two first!

Getting it

“Lighting design is a very, very intangible art form,” says Bradley King. “It only exists at that moment. You can look at a set model or a costume rendering. Lighting design only exists in space and time. That makes it harder to understand.”

Christopher Akerlind concurs. “What lighting designers do is difficult to talk about,” he says. “It’s in the past, not like a set or costumes that are onstage and later offstage, and you can look at and contemplate. Just when you want to describe lighting, it’s gone.”

Justin Townsend, Tony nominee for American Psycho and The Humans, says it helps to have a skill set when viewing lighting, just as it does when going to a museum, “but there’s also a gut intuition, and I’m most interested in asking our audiences to show up open-hearted and curious rather than saying there’s a correct way to view our work.” Townsend suggests evaluating lighting for its truth, not in the sense of verisimilitude but in terms of lighting’s connection to the story. “I’m most interested when lighting expands on what the story is doing. I’m hoping the work becomes more profound because of the lighting conversation with it,” he says, adding that lighting should be inseparable from the rest of the show. He encourages audiences to “be present and have our hearts open and ready to learn what the new rules are.”

So if theater is all so collaborative, does it matter if anyone gets lighting design?

Japhy Weideman is glad most people don’t understand what he’s doing. He wants to “create energetic environments that take people into other levels of reality. If they’re analyzing the lighting, they’re out of the story,” he says, comparing lighting to cinematography. “Most people can appreciate the experience they are having, but they’re not actively analyzing their experience. In stage lighting design just as in cinematography, there are close-ups, panoramas, jump-cuts, flash backs, and many other storytelling techniques."

“I feel that the average audience member shouldn’t need to get it,” adds Benjamin Stanton. “If all the design elements are in sync, an audience member shouldn’t be thinking ‘Oh that’s video, that’s lighting, that’s scenery. In an ideal world, all the design elements become a cohesive whole.”

But critics and nominators are another story.

“People whose job it is to identify a specific element and decide if it’s good or not don’t always recognize subtler work. The more muscular and active a design is, the more attention it tends to get. Sometimes the loudest design gets the attention,” says Stanton, who was pleasantly surprised when his understated design for Fun Home, “more akin to what you would see in a play than a typical musical,” was recognized. (Stanton is a three-time Tony nominee: Junk, Deaf West’s Spring Awakening, and Fun Home.)

“I feel very fortunate for all the pieces I’ve worked on and how they’ve been received,” Townsend says, and for “working with collaborators I admire. We’re all trying to figure out the truth of the production.”

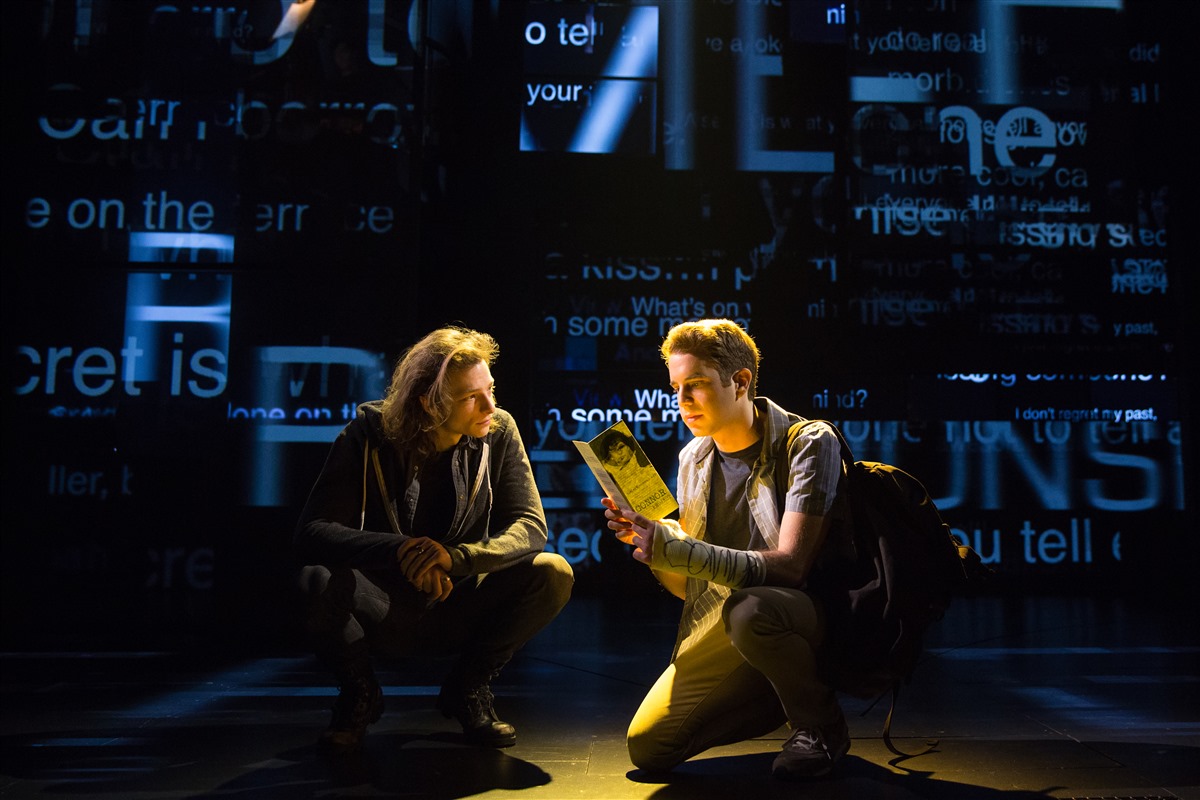

Weideman thinks that though good designers may go unrecognized by award committees and reviewers, “in my opinion, often the designers who were nominated were the ones who deserved it, although it’s often someone gets left out. It’s great if critics acknowledge that it captures a certain quality or has a certain rhythm that nicely accents the play and the direction. I had one review where I did get three sentences on the lighting, and that was great, but my job is to serve the story so if there is no mention, it’s also a compliment.” (Weideman was acknowledged with five Tony nominations: Dear Evan Hansen; The Visit; The Nance; Of Mice and Men; and Airline Highway.)

Too often, lighting design is ignored or misinterpreted. “Some critics do not understand that a lighting designer is a creator. In our culture, there are critics who have the power and voice without real knowledge,” says Akerlind, whose multiple awards include Tonys for Indecent and The Light in the Piazza, and Tony nominations for Seven Guitars, Awake and Sing, and 110 in the Shade.

“There is a famous quote from Jennifer Tipton, which I’m going to butcher, but it is something like, ‘Only two percent of people are aware of lighting design, but 98% are affected by it,’” says King, who took home the 2017 Tony for Comet. At least, he allows, it’s not a conscious awareness. “Especially as technology has advanced, lighting is more present in theater pieces than it was 50 years ago, and conscious or not, there’s an expectation,” King explains. “Audiences expect lighting to create a mood and help tell the story, and that is what lighting designers do.”