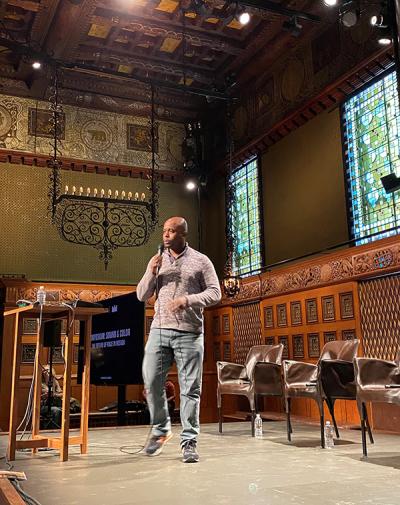

Symposium: Sound & Color started in the most engaging way possible, with the beatbox stylings and vocal theatrics of Drama Desk Award-winner, Chesney Snow. The audience, which spilled out of the historic Veterans Room at the Park Avenue Armory, was immediately enthralled. Those in attendance at the two-day conference were a mix of students, looking for inspiration and to learn from established designers, and early career professionals, such as Alex Jordan, a scenic designer working in NY. Jordan was drawn to the event looking for information, who said, “Let’s learn from those who have come before us, what can the older generation pass down to us?” He also wanted different perspectives on how to create a more equitable industry.

While one common goal of the event was to create more opportunities for design professionals of color in the theatre and events community—the subtitle for the weekend event was The Future Of Race In Design—there was some healthy disagreement on how to accomplish it. During the “Conversations Between Generations” the actor, playwright, and director Ruben Santiago-Hudson suggested that an effective route to get a foot in the door was to volunteer to work for free. Several audience members, including a working costume and wardrobe professional, called out this approach as unrealistic for most people, saying that what might have worked for previous generations was just not feasible for this one. In addition to the practical considerations of paying the rent, she suggested that a more equitable industry requires equal respect, not just equal money, and working for free can often devalue that contribution in the perception of others.

There was some consensus around the idea that BIPOC professionals are often required to work harder and more visibly than white ones and it is an approach that pays off. Lighting designer and educator Victor En Yu Tan talked about staying late and asking questions and following designers around when he was a theatre electrician learning to design. But even practical advice for established professionals to help bring in other designers of color came with a caveat: During a panel on creating a collaborative aesthetic, set designer Adam Riggs, who is a long-time collaborator with director Lileana Blain-Cruz, described his frustration that he keeps a list of diverse designers to recommend to directors and production managers, but they often dismiss it and ask for bigger names rather than taking a chance on a new designer. He said, “You have to hold the door open for others, and keep supporting their work.”

The conference kicked off with a discussion between the members of the host committee on the nature of design and the need for diversity. LD Jane Cox, set designer Mimi Lien, and sound designer and composer Mikaal Sulaiman were in conversation with playwright Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins, who described how he felt about design: “Designers hold the material world of what the playwright is holding in their laptop. Designers are the ones who bring the thing into its physical form.”

The designers noted that the next generation of designers grew up with screens in their hands and access to technology at home that they could only dream about professionally. Sulaiman said, “Technology is now more accessible—you can use garage band to create a soundscape and be part of the conversation.” Cox noted that students used to presenting themselves to a social media audience already have a perception of how to use light. But she mentions that there is racism in how lighting is taught and the technology used. She commented, “When I started teaching to a room with many different skin tones, I realized you learn about lighting by lighting a pale object in a dark space. This doesn’t make any sense anymore. What was built into our design education, how we direct attention, was reliant on old European artists. How do we teach in a way that is culturally specific?” Cox mentioned her problems lighting The Color Purple and the drawbacks of LEDs on different skin tones. “I was struggling to make Jennifer Hudson look amazing with LEDs—how can Jennifer Hudson not look amazing???”

Mimi Lien also commented on the how light and color are embedded in visual tradition. She questioned certain visual tropes saying, “The black box is entrenched in theatre language—the idea that if you paint it black it will disappear. There are a million ways to communicate mystery or evil but making it dark is the entrenched visual lexicon. How do we feel when we look at a dark space versus a light space?” Jacobs-Jenkins agreed that design shorthand in all disciplines can reinforce stereotypes, saying, “Sound doesn’t use color, but it is the most contested space historically. I’m thinking of the trope of playing loud rap music during preshow to set a certain scene.” Sulaiman agreed, saying “The trope of rap music is out of date but it was part of the message at some point. It is a thin line when you are asking a designer to bring themselves to a project or to bring their ethnicity to it. Are you being asked for your unique aesthetic or to represent some other definition of you?”

During the two-day conference topics such as Afrofuturism in Conversation with Design for Live Performance, Culturally Specific Design, and The Future of Design in XR were covered. In addition, attendees were treated to six micro-commissions presented in collaboration with Design Action. These design events were created in two days in response to the prompt: Take Space: Disrupting With Love.

Related content: