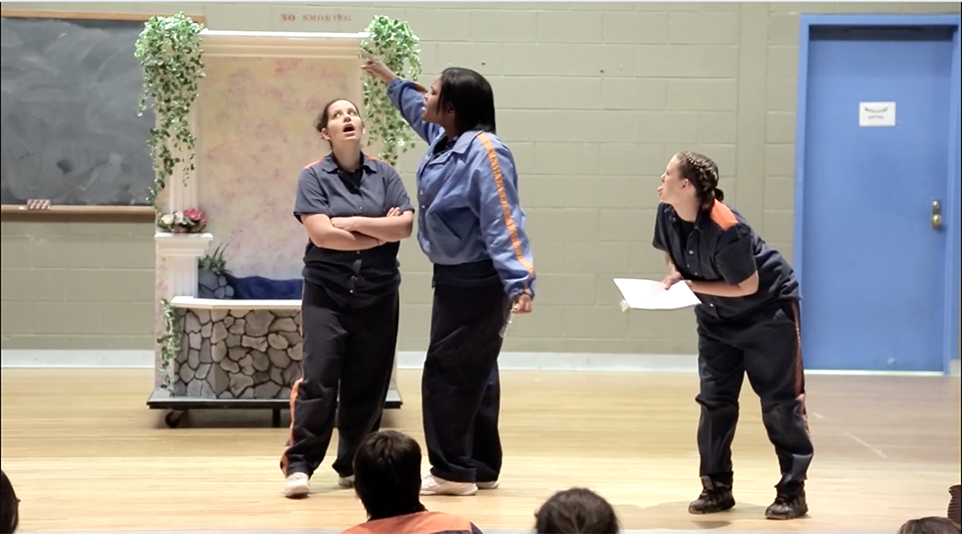

Most theaters in America have to meet multiple challenges. Almost always, there are budgetary constraints. Sometimes the playing space is inadequate, storage space is worse, shops are underequipped or far from the theaters themselves, equipment is old. Now, multiply those problems by the biggest number you can think of and you’ll have an idea of what it’s like to put on a play in prison.

Yet somehow, creative directors run theater programs in prisons. Among them is Frannie Shepherd-Bates, who directs programs in two Southeast Michigan prisons, one for men, the other for women. Casts, of course, are either all-men or all-women.

Photo by Chuk Nowak

Shepherd-Bates founded Shakespeare in Prison (SIP) at the Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility in Ypsilanti, MI in 2012. She simultaneously served as founding artistic director of Magenta Giraffe, a non-Equity theater in Detroit that did adventurous work, often with themes of social justice. Keeping a theater afloat became difficult when Shepherd-Bates began spending more time in jail—she was also pregnant—and her theater folded in 2014.

She wasn’t paid for her work at SIP then, and she had only sporadic volunteer help. Shepherd-Bates didn’t know how she could sustain or expand the program without attaching it to a university or theater. Fortunately, Sarah Winkler, who had volunteered with her at the women’s prison, was in the process of co-founding a theater in Detroit. And SIP continued under the Detroit Public Theatre’s auspices. The staff now includes a part-time assistant director and six facilitators, though director Shepherd-Bates is the only full-time staffer. In 2017, SIP expanded the work to Parnell Correctional Facility, a men’s prison in Jackson, Michigan.

Photo courtesy of Shakespeare in Prison

What differentiates this project from other prison theater programs is the staff stays in contact with alumni who have served their terms, supporting their development by helping them connect to community theaters and suggesting plays in their hometowns to see. (A couple of alumni are trying to open their own theatre; one works at DPT.) “We’re only a phone call away from moral support,” says Shepherd-Bates. They also help people find jobs, using the communication skills they developed on the inside.

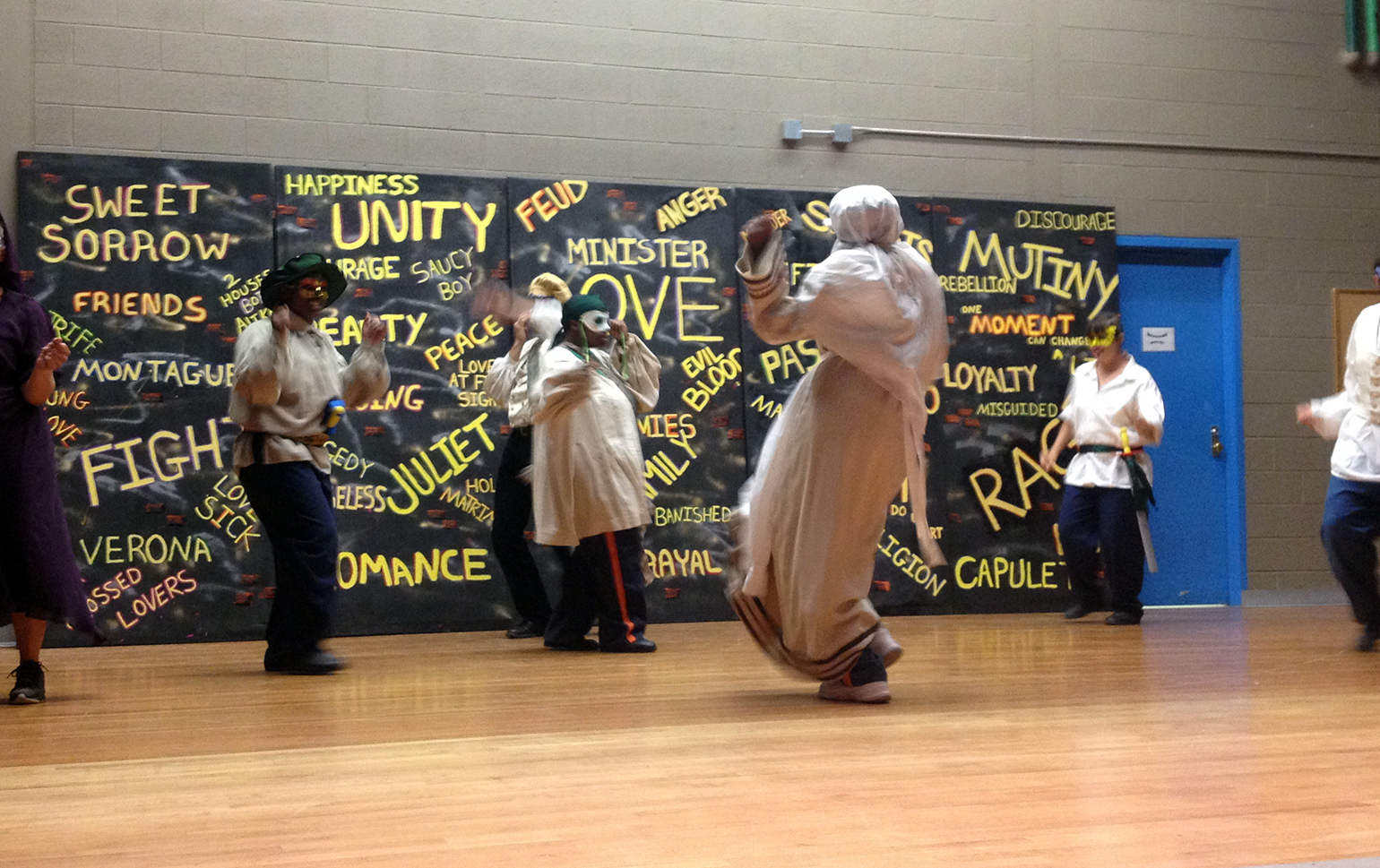

And their approach to design—well, that’s unique, too.

“Everything we do is collaborative,” says Shepherd-Bates, explaining there is no design team because “everyone is a designer.” The team collectively interprets the play, and from there, what it should look and sound like.

Photo courtesy of Shakespeare in Prison

“Our program was developed primarily by the inmates. I kind of went in and gave over ownership,” Shepherd-Bates says. “I’ve never been incarcerated. I don’t know how this works. I need your help,” she told them. The group makes cuts in the plays since they have just 90 minutes to present, eliminating what isn’t essential dramaturgically.

In addition to helping tell the story, “sets, props, and costumes are important because they lend a seriousness to the process,” Shepherd-Bates knows. But there are limits to what they can bring into the prison—anything that can be used as a weapon won’t fly, for instance. And there are limits to what they can wear, what they can do with lighting, even how they can interact.

“We aren’t supposed to have any physical contact,” former inmate Nicole Frederick says. When Romeo and Juliet touched each other’s hands, that stood for more. “We learned to work around the severe restrictions and still be able to tell the story.” Still, constraints could be frustrating, sometimes requiring that scenes be cut for non-aesthetic reasons. “You had to be mindful of the words that were used,” Frederick says. “Some of the women had suffered very violent relationships, and we had to be mindful, is this part going to trigger someone?”

Stay tuned for more in Part Two!