Extended through March 8 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), a contemporary take on Medea, written and directed by Simon Stone (based on the classic Euripides), has sets designed by Bob Cousins, costumes by An d’Huys, lighting by Sarah Johnston, and video by Julia Frey. Their technical package includes 12 Arri SkyPanel S360C and 12 Arri SkyPanel S120C, with two Panasonic PT- RZ21K projectors and QLab 4 software with a redundant MacPro hardware package.

Considered “very much of the moment” by The New York Times, this production marks its US premiere at BAM, after success across Europe. Live Design caught up with Cousins upon return to his native Australia to discuss his scenic design, which frames the production in white.

Live Design: Your designs span a wide range of disciplines (opera, dance, theatre/sets, costumes, production, etc.). How do you approach a new project in each of these areas, and especially to make a classic Greek play like Medea resonate with modern audiences?

Bob Cousins: Commonly, the text or a score is the starting point for a play or an opera. But often, work on a design begins before a script exists, and with dance, text is rarely a consideration. At other times, the director / choreographer might be drawn to a project with a particular idea or a mechanism in mind to frame a text or a dance piece. In each case, my interest as a designer is firstly the spaces in which these projects take place. My aim is always to understand and interpret these spaces for writers, directors, performers, and not least of all, audiences to find the theatrical potential of any project. Mostly, I begin a new project sitting in the dark of an empty theatre—the stage itself has a strength—anything you add to it had better earn its place.

LD: Why white? What does the "bleached canvas" represent for you? And the ashes?

BC: So much theatre takes place in the shadows. The total white of the Medea set is not metaphor but an ongoing interest in stripping away these shadows. Rather than the white, it is about the light that floods the space, placing the actors in stark relief. They demand to be seen, to be witnessed, bringing both performance and text into sharper focus. This lack of verisimilitude or illusion, is in part, an attempt to take the Medea stage back outdoors to the day-lit amphitheaters of Euripides’s Greece.

It is also in part an essay in dynamic time and space. The action no longer needs to remain linear. Again, my main interest is not with metaphor. the ash that falls is exactly that—ash. It is the physical appearance of the fire that consumes Medea and her two young boys—unfolding equally as flash-back and flash-forward, as memory and prescience, at the same time. Beyond this literal understanding, the image of the ash hopefully works like poetry, accreting its own allusions and resonances for each participant.

LD: Can you talk a little about the video screens, and how did you collaborate with the video and lighting designers...design choices?

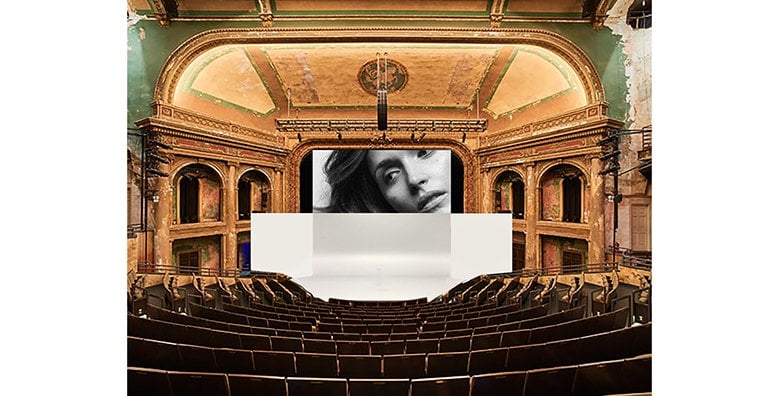

LD: The set for Medea is a shallow white room, the rear wall of which is a large projection screen approximately 30' x 15' that flies up and down often with video image, to reveal and conceal a portal into a larger, white, seamless room that sits behind the screen. There is little else, except light, which floods the total volume of the space. The source of this light is typically a series of sky panels, chosen to create an even, shadowless space. In the original production in Amsterdam, we had planned to place the video source behind a rear projection screen so that we could fly the projector and screen together. When we discovered that the light of the sky panels compromised the projection, we changed to a front projection screen and utilized a custom-built projector stand with motor that could track the video image in sync with the moving projection screen. At BAM, the projectors are fixed, and the video is mapped to the moving screen.

LD: Is this your BAM debut? How did you find working in the Harvey? Any particular pleasures or challenges?

BC: This is not the first time I’ve worked in the Harvey. I designed the set for Belvoir St Theatre’s Cloudstreet, which was presented at the Harvey as part of the Next Wave Festival for BAM in early October 2001. We arrived in NY a week or so before the premiere with a thick pall of smoke still hanging over the city. Cloudstreet was a production that had originally premiered in a vast featureless storage shed on Sydney Harbour in January 1998. Medea had its original premiere in Amsterdam in 2014 on the large open stage of the Rabozaal of Toneelgroep / ITA. Transposing both sets to the smaller, rich textured proscenium stage of the Harvey required some shoehorning and compromise. The Rabaozaal in Amsterdam has no proscenium and the original Medea set was designed to sit within a black void. In NY, we made the deliberate decision to place the stark white set unapologetically against the rich textures of the theatres—more consonance than palimpsest.

LD: What emotional response do you hope the audience will have to the Medea environment?

BC: I’m not sure I expect any particular emotional response to the set. I think ultimately any set is only a framework for the story or show.