Adam J. Thompson is the recipient of the 2023 USITT Rising Star Award. Established by LiveDesign/LDI in 2005, this annual award recognizes a young professional working in the disciplines of scenic, lighting, sound, or projection/video design. Thompson will be honored during the 2023 USITT Conference & Stage Expo, in St Louis, MO, March 15-18, 2023.

Live Design chats with Thompson about his education and his design work, as well as his advice for those entering the industry now.

Live Design: What was your educational path and when along the way did you turn to projection and video?

Adam J. Thompson: I earned my BA in directing and producing at Emerson College in Boston, and during my senior year, I founded a non-profit creative studio called The Deconstructive Theatre Project, which was dedicated to a very collaborative method of creating and producing new theatre work. In our process, all of the performers and designers were in the rehearsal room together and with elements of design from the very first day, and we all devised and wrote the show collectively. I led that company—and in the process instigated, directed, and produced theatre projects—for ten years, between 2006 and 2016. In 2012, I became interested in studying the neuroscience of memory and what role memory plays in the grieving process, and as a result, we, the company, began work on a piece called The Orpheus Variations, which used the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice as a jumping off point to explore memory both narratively and formally. In the process of exploring the way that memory functions biologically, we started to discuss the notion of the movie in the mind and the truth gap that exists between what we experience and how we remember that experience, and that reminded me of the dichotomy between the chaotic process of a film set and the beautifully constructed cinematic image that results from that chaotic process. As a means of exploring that practically, I brought some video cameras into the room and we began playing around with a live cinema and live sound vocabulary.

That project was very well-received, playing at the Magic Futurebox in Brooklyn, HERE in Manhattan, as a part of the Under the Radar Festival at The Public Theater, and as a part of the Theater at the 14th Street Y's annual season in Manhattan. Subsequent to that, and because there was such encouraging enthusiasm for the style of the work, we developed several more pieces that furthered that live cinema vocabulary, and that is how I began to become interested in— and somewhat self-taught in - using video and projection vocabularies in theatre. In 2016, I worked on a project with The Builders Association, which is a company that is very celebrated for its multimedia work and with whom I have had a long association, and on that project, I met Lawrence Shea, who leads the Video & Media Design Masters Degree program at Carnegie Mellon University. Lawrence was in the midst of recruiting new students for his three-year Masters program and he had some familiarity with my live cinema work with The Deconstructive Theatre Project. He invited me to consider joining the program the following fall, and after a series of discussions, I decided that I would like to spend some dedicated time investing in a formal education in the discipline. I earned my Masters in Video & Media Design at the CMU School of Drama, and during my final year in the program, I began receiving invitations to design in New York and regionally, and I've been doing so ever since.

LD: Can you please mention a few productions that stand out for you in terms of your work, and why?

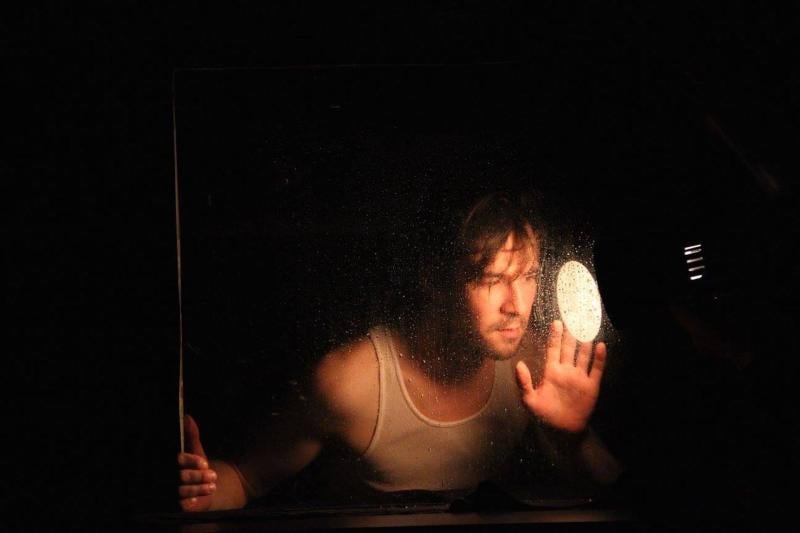

AJT: The project that I mentioned just prior, The Orpheus Variations, was a very formative experience for me, because it was the first time I had worked with video and projection vocabularies in my creative process. I have enormously fond memories of and deep gratitude for the company members of The Deconstructive Theatre Project at that time, because they really embraced this seemingly bizarre curiosity that I had about using video and cinema as a visual and formal metaphor for the behaviors of the brain during the storing and retrieving of memory. We all more-or-less designed our own crash course in the basics of video cameras and signal flows and projectors as a part of that creative process, so even though I was officially working as a director on that project, and many of the company members were performers or designers in other disciplines, we all really became mini-video designers in our own rights on that show. This was also an important formative experience for me because it taught me that video can be used as a very effective magnifying glass to enlarge, enhance, and sometimes re-contextualize the action and the materiality on stage. I really love organic materials and textures, and I fell in love with video design because of this potential to magnify those elements as well as to magnify human expressions and actions on stage. Live video work is still my favorite kind of video design, because it helps center the human in the storytelling and it cultivates a design that is an integral storytelling component rather than a purely scenographic element.

In graduate school, I designed the video for a new production of the play Alkestis, in a new translation by one of my favorite writers, Anne Carson, and directed by my fellow graduate student and friend Wesleigh Gates. Alkestis is inherently a play that is experiencing an identity crisis: it doesn't know whether it's a comedy or a tragedy or both, and Wesleigh was interested in using that identity crisis as a means of exploring other places where the production might question and blur boundaries, including the boundary between the rehearsed performers and the normally passive audience. Together, we pursued an interest in "casting" audience members in the play, and I devised an idea that consisted of seating five volunteers from the audience in a special central box which was rigged with a teleprompter system and five live cameras focused on their faces. The teleprompter fed the text from the script to the participants in real time, and the live feed cameras projected their faces onto the set as the Chorus members from the play, so oftentimes the rehearsed actors were having conversations with five large-scale faces which were projected onto and moved around a beautiful sculptural set, which was designed by the scenic designer Sasha Schwartz. I loved working on this project, because I love exploring theatrical form and creating designs that either the performers or the audience or both can interact with, and in this particular case, I was invited to really push how integrated and participatory the design could be while still keeping it controlled enough to be secure. It was also a great pleasure to work on Alkestis with a director who had similar formal interests and curiosities and with a design team that was so eager to collaborate in a very close way during a formative time in my design education.

Most recently, I designed El Paso Opera's production of Frida, and I think of it fondly as the production that refreshed my love for the collaborative potential of theatre (or in this case, opera) because the community of people with whom I worked were so wonderfully kind and open to evolving their own work in tandem with the evolution of my design. I had many conversations with Justin Lucero, who is the artistic director of EPO and who also directed the production, about how the video design could work in a way that juxtaposed the documentary tone with the more surrealistic and dream-play like tone of the libretto, and as I continued to iterate and send sketches of ideas to Justin, he would enthusiastically vocalize an openness to evolving components of his staging to meet components of the video design that I hoped to see realized. I also met and worked with the wonderful scenic designer and director Afsaneh Aayani on Frida, and we have since become good friends, and both Justin and Afi and I already have other projects on the burner together.

The Frida experience reminded me how important it is to "find your tribe" of collaborators and how wonderful a creative experience can be when you're working with people who are kindred spirits. The Chavez Theatre in El Paso, where we presented the opera, is an enormous space with an enormous stage, and it was also exciting for me to design for and then see my work realized on such a large canvas.

LD: How do you research images for a production?

AJT: I'm a big history nerd, a big old cinema fan, and I collect historical ephemera, so when I first take on a project, I often first read up on the history of the time in which the play was written (if it's an existing play, musical, or opera) and also the time during which it's set, look at design trends from advertising and ephemera from the period, and also research the visual aesthetics and conventions of cinema from those time periods - that often includes the style of title sequences as well as the types of shots and editing used in the films themselves. Many older films in particular have really evocative title sequences which do an excellent job of distilling the aesthetics of a moment in time into a very concise package. I live in New York, and I also like to take walks around the city in order to discover surprising juxtapositions of imagery and ideas. I take lots of photos and save lots of imagery from Instagram that I find aesthetically exciting on a daily basis, even if they aren't directly related to a current project, so that the next time I'm feeling blocked while working, I can turn to this bank of imagery for inspiration.

LD: What software do you use in your design and production process?

AJT: I use what I suppose are some of the typical pieces of software like the Adobe Creative Suite (Photoshop, Illustrator, After Effects, etc) for image and animation creation and Cinema 4D for 3D content. I am very interested in historic preservation and I have an ongoing project 3D scanning urban landscapes and ruins using a workflow that combines Photogrammetry software like Agisoft with game design software like Unity, which allow me to both construct and navigate around 3D digitizations of environments and buildings. I most enjoy software that are designed as a sort of creative sandbox meant for creating interactive systems, like Max and TouchDesigner, and I've spent a little bit of time getting to know Notch, which has really exploded into the field over the past couple of years. I love Millumin for running shows - it's an incredibly robust and flexible media server program that runs on Mac computers. I always say that it's the Swiss Army Knife of playback software, and I have used it in everything from installations for one person to giant corporate shows for Fortune 500 companies.

LD: What advice would you give young designers getting into the biz today?

AJT: My first piece of advice is to know yourself: reflect and discover what excites you narratively, dramaturgically, and aesthetically, and look for ways to bring those passions into your creative process. One of the beautiful things about making theatre and its associated art forms for me is that every project is a new world, but I also always want to bring my unique sensibilities and experience of the real world into my designs, too. I've often said that, for me, the definition of "art" is no more than "one person or group of people showing another person or group of people how they experience the world," and I think it's really important that a designer—or any creative practitioner—doesn't completely subsume themself to the world of the play; enjoy the exploratory process of merging the world of the play with your own experiences and aesthetics on the journey to realizing one holistic design.

My second piece of advice is to know and appreciate your value and to stand up for it. Don't work for free. Consider the amount of time and money that you have invested in your education and the experiences you have had that have led you to where you are now, and be able to clearly articulate why and how you will be a valuable collaborator. Similarly, if you are engaged in a project and feel you are not being treated justly, speak up. I have found among young designers the fear that rocking the boat will lead to career ruin, and I think it's really important that we empower young creative professionals with the confidence to advocate for themselves without fear.

Third, be a generative force. I think that unfortunately designers are often thought of as secondary artists, by which I mean we are often brought into a project after a writer or a director or a producer has an idea and is subsequently seeking out designers; but designers certainly have ideas, too, and we often have them from the unique points of view of our specialized disciplines. So if you have an idea that excites you, seek out collaborators and make it happen. I think too often we are asked to "be" one thing professionally, but creativity transcends boundaries and a designer can certainly also be a director or a writer or a producer or just explore different elements of those identities in their own practice, as well.

I think it's also very important to push against the idea that making "art" is a noble profession, while making money is a form of selling out. This is a simplification, of course, but in my experience this idea is out there, especially among young artists. There are so many practical environments in which the skills of a designer in any discipline are useful and would be valued, and they run the spectrum from experimental performance-making, to commercial theatre, to museum exhibition design, to experiential marketing, to corporate sales events, and beyond. Unfortunately, the arts are not well-supported in the United States so making a comfortable and safe living requires exercising a certain amount of creativity and building a diverse professional portfolio. Any environment in which you can practice and share your talents and passions is a worthwhile investment, and working across fields is also a wonderful educational experience.

And finally —and this is a piece of advice for myself, as well—never stop looking for your tribe, your creative kin. Some projects we do for experience, some projects we do for financial stability, some projects we do because we love what they have to say, and some projects we do because of the people involved. In very lucky circumstances, we do a project that has several of these attributes, but in my experience, I have always had the most enjoyable, fulfilling, and mentally and creatively robust experiences because of the people involved, and especially when they are repeat collaborators. When you find those people, make a point of telling them how much you admire them and enjoy working with them, and make mutual commitments to work together. I think creativity is a very human endeavor, and it's most rewarding when it involves forging connection and building community.

Related article: Adam J. Thompson To Receive 2023 USITT Rising Star Award Sponsored By Live Design/LDI